Poor Charlie's

Almanack: The Wit and Wisdom of Charles T. Munger

About Author:

Charles Thomas Munger (born January 1, 1924) is an American

investor, businessman, former real estate attorney, and philanthropist. He is

vice chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, the conglomerate controlled by Warren

Buffett; Buffett has described Munger as his partner. Munger served as chairman

of Wesco Financial Corporation from 1984 through 2011. He is also chairman of

the Daily Journal Corporation, based in Los Angeles, California, and a director

of Costco Wholesale Corporation.

Summary of Book:

People in general, think that the individual investor

doesn't stand a chance against the professionals. Pointing to high-frequency

trading and the complexity of the financial instruments that Wall Street has

become renowned for, many argue that this must be true. And besides, why would

the professional analysts have such high salaries otherwise?

In this book Burton Malkiel argues that this couldn't be

further from the truth! He shows that even a blindfolded monkey throwing darts

at stock listings would outperform their professionals. Fees, taxes, human

psychology, and most of all that markets behave like a random walk, are stated

to be reasons for this. This is an extremely controversial topic, as you

probably can tell already. And the stakes are high. Banker's bonuses all over

the world are threatened.

Fasten your seat belt, for the following takeaways won't be

any less provocative!

Takeaway #1:

Fundamental analysis doesn't outperform the market:

In beating the market, professionals tend to rely on one of

two strategies: The fundamental approach or the technical approach. The

investors who use fundamental analysis as their vehicle for earning money in

the market, believe in the so-called "firm

foundation theory" This theory argues that the price of an investment

is anchored is something called "intrinsic value", and that the price

of an asset typically over or underestimates this value.

The task of the fundamentalist is therefore to buy assets

that have an intrinsic value higher than the current price of the asset, and

sell if the opposite is true. The intrinsic value can be determined by

discounting all the future cash flows of an investment. Discounting is the

process of turning future earnings into today's value.

Remember that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar

tomorrow! To calculate the correct intrinsic value of a stock, a fundamentalist

must assess the following 4:

1.

Earnings

growth rate. The most important part of the calculation revolves around the

estimation of future growth rates of earnings.

2.

The

expected dividend payout. The higher the dividend payout, the greater the

value of the stock, everything else equal.

3.

The

degree of risk. Everyone prefers an investment with a lower risk of losing

money over an investment with a higher risk of losing money, even though the

expected returns are the same.

4. Future market interest rates. I stated earlier that a Swedish crown today, is worth more than a Swedish crown tomorrow. But I didn't state how much more. The so-called "risk-free rate of return", which is decided by the interest rate of the three-month US Treasury bill for US investors is used as a baseline for this. The higher the risk free rate of return, the higher the return should be expected from any other investment

Perhaps you already see some of the problems ...

1.

Faulty

information. The information given by the company you are interested in

acquiring could be misleading. This has been common, especially during times of

mass optimism, such as during the dot-com bubble. In these situations CEO could

mean "chief embezzlement officer", and you can't be sure where the

CFO is a "corporate fraud officer" or not. Also the EBITDA in the

income statement might be an acronym for "earnings before I tricked the

dump auditor". All kidding aside, there are many cases where reported

earnings, assets and the likes are misleading, which makes it very hard for the

fundamentalist to predict the future. Any computer scientist knows that garbage

in means garbage outs.

2.

Errors

and wrong conclusions in the analysis. Even if the information given to the

fundamentalist is trustworthy, he's still faced with the daunting task: He must

make predictions about the future without the benefit of divine inspiration. He

must use the information available without conducting errors or drawing the

wrong conclusions.

3.

Influence

of unexpected events. The fundamentalist might use all the current

information available to assess a perfect analysis of the stock, only to find

out later that the company's primary production plant was hit by an earthquake.

Or that the CEO, and the founder of the company, dies of a sudden heart attack.

Approximately 90% of the analysts on Wall Street are fundamentalists.

Takeaway number 2:

Technical analysis doesn't outperform the market either:

Technicians, as the people believing in a technical analysis

are called, trust in the "castle-in-the-air theory". As opposed to

the fundamentalist view, this theory argues that intrinsic value is of less

importance. Instead, what's most important is the behavior of the investment

community. Crowds do not act rational, and they are susceptible to building

castles in the air in the hopes of acquiring wealth. A successful investor's

primary task is therefore to estimate which investments that are most prone to

castle building. A sucker is born every minutes and the technicians task is to

buy investments that later can be sold to these people. If someone else is

willing to buy higher, the price you pay matters not! Dutch tulip bulbs during

the mid-1600s, conglomerate's in the late 1960s and Internet stocks in the

early 2000s, are great examples of castles in the air. The technician will use

charts of stock prices and trading volume to determine future prospects of

castle building. There are 3 primary reasons as to why technical analysis is

stated to work according to Malkiel:

1.

Price

increases are self-perpetuating Increases in price tend to cause additional

increases. People can't stand waiting on the side-lines when others are

making money. Therefore, demand increases with every price increase which

causes prices to go even higher, creating a dangerous upward spiral.

2.

Unequal

access to information. Insider's are the first to know about changes in a

company. Then comes the friends the families of these people, then the

professionals and their institutional capital and finally, poor people like you

and me. Charts are supposed to give information about when either insiders or

professional are buying, so that you can make your move before the rest of the

market does.

3.

Investors

underreact to new information. The stock market will react to new

information gradually, which results in longer periods of sustained momentum.

Malkiel, and other advocates of the random walk counter argues with: 1: Sharp reversals Uptrends can

happen drastically, which may cause the technician to miss the boat. When an

uptrend is signaled, it may already be too late. 2: Profit maximization. Let's say that company A's stock is at

$20.

One day, it develops a new product that increases the value

of the company to $30. Before releasing this information, wouldn't it make

sense for the insiders to buy the stock until $30 has been reached? Every

dollar they invest before $30 is an instant profit! 3: The techniques are self-defeating. Once people know about the

techniques that are supposed to efficient, the technicians will compete each

other out.

Other traders will try to anticipate certain signals that

they know that everyone else is buying or selling to. Approximately 10% of the

analysts of Wall Street are technicians.

Takeaway number 3:

Human psychology makes it even more difficult to beat the market:

As if the aforementioned reasons weren't enough, there are 4

factors that professionals and individual investors alike face when they are

trying to beat the market, which further reduces their chance of doing so.

Overconfidence:

This bias causes mortals like us to be over optimistic about assessments of the

future, and to overestimate our own abilities. Thereby, we conduct sloppier

analysis and take higher risks than otherwise would have been the case.

Biased judgments:

Humans tend to think that they have some control in situations, even though the

situation is completely random. Technicians are argued to be especially

vulnerable to this as they think that they can predict future prices by looking

at past ones.

Herd Mentality:

This might be the most obvious one. Herd mentality is the primary reason for

many of the stock market's greatest bubbles and following meltdowns. When your

friends all brag about their latest stock profits and the news of predicting

economic "golden ages", it's hard if not impossible, to stand idle on

the side-lines.

One great example of this is group thinking. Individuals can

influence each other into believing that an incorrect point of view is, in

fact, the right one Loss Aversion.

Lastly, loss aversion

is another psychological factor that makes it difficult to us to stay rational

in the market. Losses are considered far more undesirable than equivalent gains

are desirable. Consider the classic game of a coin flip. Heads, you lose $100,

and tails, you win $100. Do you want to play? Most people don't. Studies have

shown that the positive payout had to be 250 dollars before people were ready

to take this gamble. You can only imagine the consequences that this results in

for us in the stock market.

Takeaway number 4:

The random walk and efficient market hypothesis:

Now, if neither fundamentalists nor technicians can predict

the market, who can? According to the author, no one can! Why? Because the

development of the market is a random walk. A random walk is one where future

steps or direction cannot be predicted by history. Based on this concept of the

random walk, three versions of the so-called "Efficient Market

Hypothesis" have been developed.

Weak EMH: The

market is efficient in the way that it is reflecting all currently available

price information. If there are obvious opportunities for returns, people will

flock to exploit them until they disappear. The weak theory suggests that

technical analysis can't be used for beating the market, but that fundamental

analysis might be able to.

Semi-strong EMH:

The market is efficient in the way that it is reflecting all publicly available

information. This would mean that an investor cannot beat the market by either

technical or fundamental analysis. The only way to stay ahead of the curve

according to its advocates is by using insider information.

Strong EMH: The

market is efficient in that it is always mirroring the true value of an asset.

In this case even insider information wouldn't help you trading stocks and

earning above market returns. People often joke about supporters of the

efficient market hypothesis by telling this story: A professor and his students

was walking down a road when the student suddenly spots a $100 bill. He stops

to pick it up, but is interrupted by his professor. "Ah, don't bother

picking it up boy. If it truly was 100 dollar bill, it wouldn't be laying

there." The author of this book is not a believer in this strongest form

of the efficient market hypothesis. But rather he would answer his pupils

something along these lines: "Hurry up and pick it up boy. If it's truly a

hundred dollar bill, it won't be laying around for long."

Takeaway number 5:

How you can beat Wall Street:

Because of the flaws of the two primary strategies of investing

and because of human psychology, Wall Street professionals have been unable to

beat the market historically. This can be proven by making a very simple point:

An investor who puts $10,000 in the

S&P; 500 market index at the beginning of 1969 would have $736,000 in 2014,

compared to an investor who puts his money in the average actively managed

fund, who would end up with "only" $501,000. When it comes to

investing, you get what you don't pay for! Herein also lays the solution on how

to beat Wall Street: Invest for the long run, and in cheap index funds

primarily.

There are other asset classes to consider as well, to

increase diversification and decrease your risk. Here's a lifecycle-guide on

how to invest to beat "The Street". Mid-20s, Late 30s, Mid-50s, Late

60s, and beyond. This might sound too simple to be true, and it actually is.

You must also consider these 5 core principles for asset allocation:

1. Risk and

reward are related Anyone would pick $100 guaranteed before a $200 coin

flip. Risk in the stock market is defined as the volatility of the individual

investment. Volatility is measured by how much the return typically differs

from its expected value. A higher volatility means a higher risk that you might

be forced to sell with a loss at a later stage and may imply that your

investment has a higher risk of defaulting

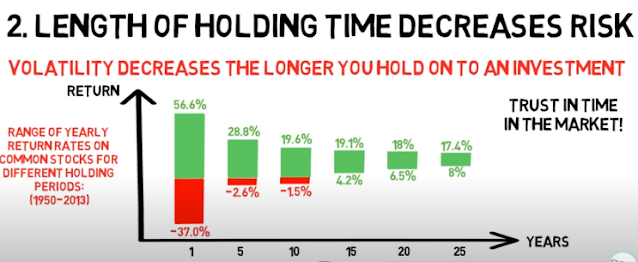

2.

Length of

holding time decreases risk. The longer you hold on to a position, the more

likely that it will perform according to its expected value. In other words,

the longer you can hold on to an investment before you need that specific

money, the less risk you take! This is best illustrated by the following graph

which shows how much yearly return different holding periods in stocks resulted

in during 1950 to 2013. Notice that when holding stocks for at least 15 years,

there wasn't a single period of negative returns. Trust in time in the market,

rather than timing the market!

3.

Use

dollar cost averaging. Dollar cost averaging means investing the same fixed

amount at regular intervals. For instance, put 10% of your salary in an index

fund every month. By doing this you will benefit from the up- and downswings in

the market. Your average price per share will actually be lower than the

average price at which you bought them. Why? Because you'll buy more shares

when the market is cheap and depressed and less of them when it's expensive and

over-optimistic.

4.

Decide

your tolerance for risk. How much risk you can tolerate depends on your

financial situation, your age and your psychology. If losing your investment

money, means that you will have to drastically change your lifestyle, as in the

case of a retiree living from his or her investment income, you might want to

downsize risk. Similarly, if your sleep is affected by the volatility in your

stock portfolio, you might want to "sell down to the sleeping point"

as JP Morgan once suggested to a friend.

5.

Rebalancing

can reduce risk and possibly increase returns. Let's say that you're a 25

year old. You are then suggested to keep 70% of your assets in index funds, and

15% in bonds, according to the examples presented before. If stocks have been over

performing lately, you might end up with 80% index bonds and 5 percent bonds.

Here's a quick recap: Takeaway number 1 is that fundamental

analysis has a tough time beating the market and the 2nd takeaway is that

technical analysis doesn't seem to be a winning strategy either. Number 3 is that

beating the market is made even more difficult due to human psychology. 4 is

that future market development is essentially a random walk and therefore it

cannot be predicted. The final takeaway is a hopeful one for the individual

investor, as it suggests that he can easily beat the average analyst on Wall

Street, by simply buying and holding the market index. This was only a fraction

of what the more than 420 pages of "A Random Walk Down Wall Street"

has to offer.

Comments

Post a Comment