The Snowball: Warren

Buffett and the Business of Life

About Author:

Alice Schroeder (born December 14, 1956) is an American

author and former insurance analyst. In the first week of October 2008, she

published The Snowball, Warren Buffett and the Business of Life, a The New York

Times Bestseller List bestseller. As a project manager for the US FASB, she

managed SFAS No. 113. Since 2008, Schroeder has worked as a columnist for

Bloomberg News.

Summary of Book:

Warren Buffett is arguably the most successful investor of

all time. He has been averaging approximately a 20% growth of his capital per

year, which has turned his small fortune of a thousand bucks in the early

1940s, into quite an outstanding one of 86 billion as of 2018. In 2007, he

became the richest man in the world for the first time, and lately he's been

having a back and forth with the likes of Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos. His

complete focus on investing can't be overstated. He always tried to save a buck

in order to grow his capital faster, not interested in real estate, art, cars,

or any other tokens of wealth. He still lives in the same old house which he

did 50 years ago. During his honeymoon together with a young Susie Buffett, he

travelled the US with a car stuffed with annual reports and Moody's manuals. He

basically never stopped studying. .

Let's get started with the takeaways!

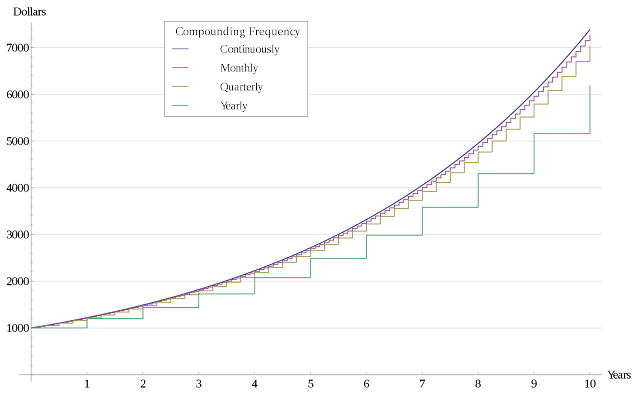

Takeaway number 1: The power of compounding income:

Imagine that you recently started a new job. During your

first day, you work for 8 hours and at the end of the day your manager gives

you $100. The next day, you go back and you get ready for another 8 hours of

labor. After 7 hours and 50 minutes, your manager goes over to you, gives you

$100 and asks you to leave for the day. You're slightly confused, but don't

complain about being able to quit 10 minutes earlier. On day 3, the procedure is

repeated - only this time your manager gives you a hundred bucks after 7 hours

and 40 minutes. On day seven, when your manager hands over your salary after

only 7 hours, you feel that you must ask what all this is about. Why do you

keep earning the same amount, but with less effort? Your manager simply gives

you the following explanation: "Because you worked yesterday!"

This example illustrates the power of compounding income.

Money comes easier and easier the more you have of it, or as in our example, the

more that you've worked previously. Warren Buffett understood the importance of

this at an early age when he was presented with the book "1000 Ways to

Make a Thousand Dollars". He was fascinated by one of the business ideas

of the book, which was to buy weighing machines. You get paid by taking out a

small fee every time someone wanted to use the machines. Once you've gained

enough money from weighing people with the first scale, you can now buy a

second one, and earning money for the third one will go twice as fast!

Warren Buffett used this approach early in his life, but the

business consisted of pinball machines, not weighing machines. In this, he also

discovered the miracle of capital - money that works for its owner. He used the

power of compounding income to his advantage in forming his first investing

partnership - Buffett Associates. The deal was that he would gain half the

upside, above a 4% gain, but pay a quarter of the downside to his partners. We

have a hard time seeing the fund managers of Wall Street exposing themselves to

such a risk of losing capital. But in Buffett's case, this was a calculated

risk that accelerated his compounding even further.

By turning his company Berkshire Hathaway into an insurance

company, Buffett has been using compounding to his advantage for many years

now. You see, insurance premiums are always paid before the actual claims might

come, which gives Buffett plenty of time to compound the money before an

eventual payout. According to the saying: If

someone dropped a dollar, the average billionaire wouldn't bother picking it

up, because the money gained from doing so is less than what he usually earns

during such a timeframe. Warren on the other hand, would gladly pick it up

and state: "This is the start of my next billion!" That's the power

of compounding.

Takeaway number 2: Be very skeptical of new paradigms:

"New paradigm is like new sex - there just isn't any

such thing!" In 1999, just before the dot-com bubble went burst, people

spoke about a "new paradigm" when referring to the stock market. Many

expected returns averaging 20% per year, and they thought that Buffett was

crazy who didn't want to buy the hyped up internet stocks. Buffett was VERY

skeptical, and explained that there are only 3 cases in which high valuations

like these ones could be motivated:

1. Interest rates are low and

will continue to be so, or decline even further.

2. The share of the economy that

goes to investors increase. In other words, employees and the government get less.

3. The economy starts to grow

faster. He added that during the current circumstances, this was wishful

thinking. The market is a voting machine in the short run and a weighing

machine in the long run. There's no literacy test that leads to voting

qualification, which the market proves over and over again. But eventually -

weight will count.

Ultimately, the value of the stock market can only reflect the output of the economy. Between 1964 and 1981, the Dow Jones Industrial Average stood still. At the same time though, the economy grew five fold! Why would investors pay the same price for something that generates 5 times the money?

Well, simply because they thought that the rules of the game had changed in 1964 - and they paid a high price for thinking so. Herd mentality makes it easier said than done to be skeptical when we enter into bubble-like valuations. It's simpler to go through life as the echo - but only until the other guy plays a wrong note.

You are neither right nor wrong because people agree with you - you are right because your facts and reasoning are right. During times of wacky valuations, it helps to be guided by an "inner scorecard" rather than an "outer scorecard".

Consider this:

Would you rather be the world's greatest lover, but have everyone think that

you're the world's worst lover, or would you rather be the world's worst lover,

but have everyone think that you're the world's greatest? If you would pick the

previous option rather than the latter one, you are guided by an inner

scorecard, which is very helpful in resisting to participate in the madness

that the market sometimes displays.

Takeaway number 3: Stay within your circle of competence:

According to the story: A man was able to corner the market

of shoe buttons - a very small and niched market, but he had all of it. Once he

had accomplished this, he imagined himself as the expert of basically

everything! While among his friends, he always knew best. Whether they were

discussing relationships, love making, health, or, or any other topic for that

matter.

Because of his expertise in one area, he thought he was a

master of everything. Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger, his right-hand man,

referred to this as the "shoe button complex". Buffett attributes

much of his success to the fact that he was able to avoid this, and instead

stay within his circle of competence - money, business and his own life. For

instance, Buffett could have pursued his grandfather's dream of becoming an

author, but did not.

Luckily, within the field of investing, this is especially important. Buffett explained it like this: "We will not go into a business where technology - which is way over my head - is crucial to the investment decision. I know about as much about semiconductors or integrated circuits as I do of the mating habits of the anything else. You are investing in business, not a stock.

Remember this well and see to it that you understand what kind of company you are actually buying. This could mean that you want to focus on industries aligned with your education. For example - a medical students might want to invest in health care and pharma stocks, while an electrical engineer might want to focus on the energy sector. This could also mean that you want to invest more of your money in your domestic market, or companies exposed to your domestic market, as you understand the business environment there better.

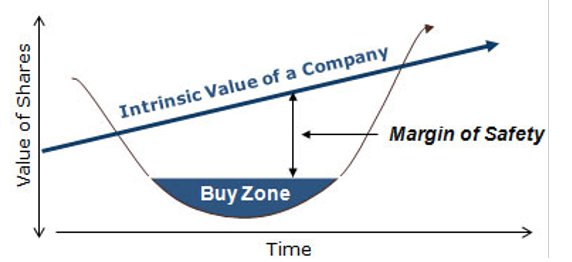

Takeaway number 4: Use a margin of safety

Let's pretend that you're a construction engineer. You've been assigned with the task to build a bridge. The bridge is a very complex one, especially the calculations regarding the carrying capacity. You've been told that the trucks passing your bridge sometimes will weigh as much as 40 tons. Will you build a bridge so that your calculations say that it supports 41 tons, or 60 tons?

If you picked 41 tons, this could be a possible scenario: You made a small mistake in your calculations. So your bridge could only carry 38 tons in reality. Now this really heavy truck tries to drive across it ... Not so nice, eh? Sure an accident could happen if you try to build one which supports 60 tons as well, but the risk is reduced.

Let's face it - our estimations when trying to predict the future of a stock, we need plenty of room for error - a margin of safety. If you think that a stock is worth $50, you don't buy it if it also costs $50 in the market. In this situation, you might want to wait until the stock costs $40 instead, assuming that you still think its value remains the same at that point, of course.

Warren Buffett understood this early, thanks to his teachers Benjamin Graham and David Dodd. The margin of safety helps so that your profits from good decisions are not wiped out by the losses of your errors. A certain category of stocks that fulfills the margin of safety, which Buffett liked to invest in during his early career, are the so called "cigar butts". These are cheap and unloved companies.

They aren't the best ones, but they're often good for one more "puff". Buffett learned this approach from Graham as well. He looked for companies that will be worth more dead than the current price of the stock. Meaning that, if all the assets of the company was sold and it closed, the shareholders would earn a profit.

For such a company, the operating business is essentially free! Buffett never abandoned this approach of a marginal safety. This is also why he could stay ahead during many of the most speculative bubbles in the market. If he couldn't find companies that fulfilled his criteria - he stayed in cash. He didn't join the herd when it was heading for the slaughter that is the peak of a bull market.

Takeaway number 5: Invest where there's a toll bridge:

Graham had taught Buffett to be a true value investor and focus on cheap and disliked stocks. In 1959, when Buffett met Charlie Munger for the first time, this would partly change. Munger was more focused on the competitive advantage of a firm over time.

The idea with the "toll bridge" is that once the initial investment is made, that is building the bridge, the tolls can be increased in a monopoly like fashion - because there's no other simple way of receiving a similar solution for the customers, that is getting to the other side of the bridge. At one point Buffett and Munger actually owned 24% of a bridge which connected Detroit and Windsor.

With such a business, you could be stranded on a deserted island for years without having to worry about your investments. Buffett summarized it in this statement:

"It's far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price, than a fair company at a wonderful price."

Let's look at examples of toll bridges: Brands Coca-Cola has, through its brand, secured profits for many years ahead. Even if someone would manage to create a better tasting soft drink than Coke, they need to spend billions in advertising to be a threat. Network effects: All social media platforms are great examples here. YouTube and Facebook become more and more valuable for each individual user, the more users there are on the platform. It wouldn't be so fun on YouTube without any content creators, right? Therefore, a new entrant in the market, which by definition must be small in the beginning, can't deliver the same value, and therefore never gets a chance to grow.

Stickyness: When customers face high switching costs, changing from company A's product to competing company B's product, company A tends to be a good investment. Such an example is the enterprise software company SAP. Its products take significant time, effort and money to learn. So once you understand them, you don't want to start all over by switching to the product of another company.

High set up costs: If it takes a significant amount of money just to serve the first customer, competitors usually hesitate before entering the market. Railroads and electrical grids are great examples. Setting up a second rail, or a second grid next to the already existing one is a game of very, very high stakes.

Warren surely seems like a smart guy, right? Now, follow his advice so that you all can become great investors as well! happy reading!

Comments

Post a Comment